Sacks, Lovecraft and the Door

Sacks, Lovecraft and the Door

This piece stems from a discussion I had at Cicchetto e Libretto, a book club that meets in Base in Palazzolo (BR) once a month to discuss a reading and choose the next one. I found no one who had written about this parallel, and since it seemed like an interesting parallel to me, I decided to throw the first stone.

Oliver Sacks (1933-2015) dedicated his career as a neurologist to documenting the bizarre ways in which the human mind can malfunction. In “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” he presents Dr. P, a music teacher with visual agnosia so profound that he couldn’t recognize faces, including that of his wife, whom he once tried to lift onto his head, mistaking her for his hat, giving the work its title.

In a parallel world, H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) tells of cosmic horrors in which protagonists encounter entities and geometries so alien as to drive observers to madness. In The Call of Cthulhu he describes architectures with absurd angles and non-Euclidean geometries, structures that the human mind simply cannot process.

A common theme: what we experience as reality is simply a construction of our neural architecture and this construction is terribly fragile. When Dr. P looks at a glove and calls it “a continuous surface with five outward protrusions”, he is living the exact same experience of alienation from reality that Lovecraft’s characters experience before losing their sanity.

Understanding how easily our perception can be distorted forces us to question what we take for granted as real. If a small neurological fault can transform your wife into a hat, or if encountering non-Euclidean geometry can destroy your sanity, then perhaps reality itself is less stable than we imagine.

The Door

Imagine being in an empty room, no bed, no furniture, nothing on the walls. You’ve never needed to sleep or eat. One day, passing your hand over one of the walls, you realize that the wall is not smooth. You follow with your hand the ripple you feel, right angle after right angle you realize that there’s a door in the wall. What do you feel? What does the existence of this door tell you? The simple existence of that door is enough to change your world forever, no matter whether you open it or not.

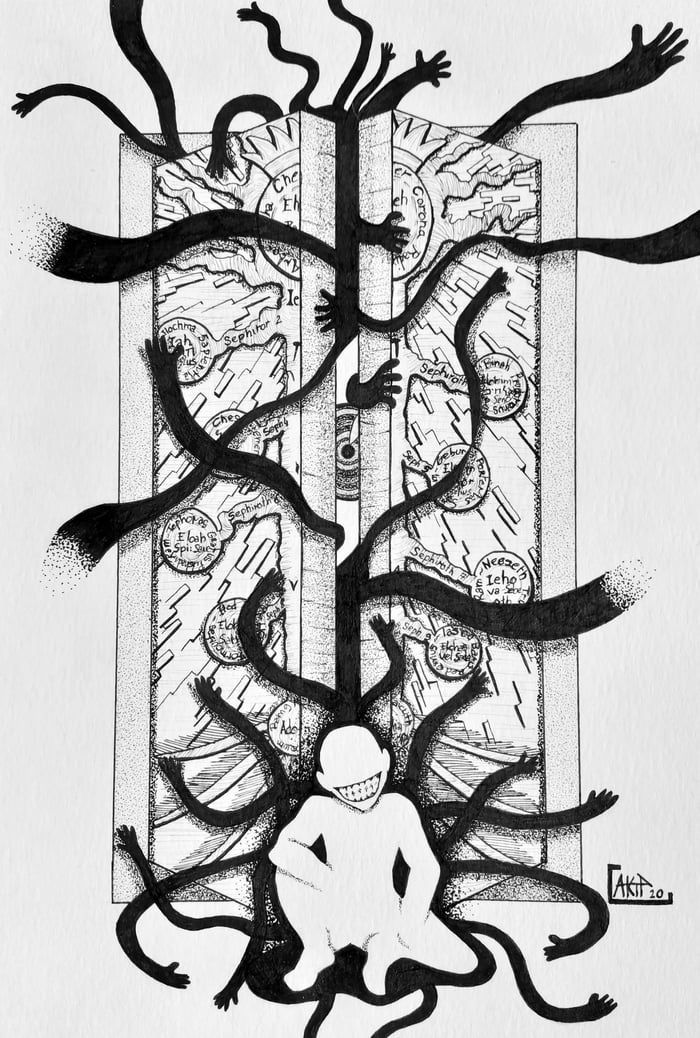

Both Sacks and Lovecraft extensively deal with moments and limits beyond which normal perception fails. Doors between comprehensible reality and the abyss that lies beyond.

In Sacks’ clinical observations these doors manifest as neurological boundaries: the patient with visual agnosia can no longer enter the room of facial recognition, the woman who loses proprioception can no longer feel her body in space; she has crossed a threshold into a state where the most intimate aspect of existence, being physically oneself, becomes alien.

Lovecraft in “Dreams in the Witch House” tells us about a mathematics student who discovers that certain angles in his room can serve as portals between dimensions. In “From Beyond,” a scientist creates a machine that allows humans to perceive realities that exist alongside ours, with terrifying consequences.

What unites these perspectives is the recognition that crossing such thresholds fundamentally transforms the perceiver. Once you have seen beyond the veil of normal perception, you can no longer not see it. Sacks’ patients must adapt to their new realities; Lovecraft’s characters typically go mad or die, unable to integrate what they have experienced.

Phenomenologies of Collapse

Perhaps the most intimate horror is when our own bodies become foreign to us. Sacks describes Christina, “the disembodied lady,” who lost all proprioceptive sense, the ability to feel where her body exists in space. She described herself as “skinned like a frog,” and complained that her body felt dead, unreal, not hers. Without continuous visual feedback, she couldn’t move or even maintain posture.

Both authors reveal that our most fundamental sense of reality is based on fallible neural processes. When they do, the result is profound existential horror. Lived experience both in a neurological ward and in the fictional city of Arkham.

Sacks’ patient, Dr. P, couldn’t recognize faces: not that of his wife, not those of his students, not even his own in the mirror. Instead, he identified people by isolated features or by their voices. When shown a photo of Einstein, he didn’t recognize the iconic face but “the mustache, the hair.” The world became a fragmented collection of features rather than coherent wholes.

Lovecraft’s entities are frequently described as having features that human minds cannot process as faces. The most famous, Cthulhu, has a head “with features that recalled an octopus, a dragon and a human caricature… but it was the general outline of the whole that made it most frighteningly terrifying.” Other entities are described as having “a face that was not a face” or features that change when observed.

Both scenarios produce the same unsettling effect: the collapse of our ability to recognize the most basic social anchor, the human face. Without this ability, the world becomes profoundly alien. Sacks addresses this clinically; Lovecraft exploits it to generate horror. But both are documenting the same neural abyss.

Sacks documents patients with parkinsonian disorders who experience time as frozen or accelerated, as well as those with temporal lobe epilepsy who experience eternal moments or déjà vu so intense it seems prophetic.

Lovecraft was obsessed with temporal distortion. In one story the protagonist’s mind is switched with that of an alien from the distant past. In another, non-Euclidean geometry allows travel through time. His entities exist beyond time or experience it non-linearly.

When perception of time crumbles, causality itself breaks down. This is perhaps the deepest perceptual break of all, where not only objects or bodies become alien, but the fundamental structure of experience itself.

Who Opened the Door

Sacks and Lovecraft really diverge in what happens to those who, by mistake, open the door. For Sacks it seems that more often than not there is an adaptation of subjects to their condition. Dr. P, unable to recognize faces, developed an elaborate system to recognize people by their voices, their hair, their movements. Christina, lacking proprioception, learned to control her movements through constant visual support, effectively replacing one sense with another. These patients build new realities to replace what they’ve lost and in some cases gain extraordinary abilities.

For Lovecraft, even just surviving is a miracle. His protagonists typically descend into madness, commit suicide, or are destroyed by what they’ve encountered. The few who survive do so through compartmentalization, literally forgetting what they’ve seen, or embracing a new non-human perspective that makes them alien to others.

This divergence reveals an philosophical divergence: Sacks’ humanistic belief in adaptation and resilience against Lovecraft’s cosmic pessimism. Yet both recognize that once perception is fundamentally altered, there is no return to normality, only moving forward in a new reality. People who have opened the door either forget about it or cross through it without being able to return.

Melt my eyes, see the future

The history of humanity is a history of both external and internal search, and since we have memory we have sought something capable of altering our sensory perception and cognition, whether substances, meditation or sensory deprivation. Both authors confront this impulse to peek behind the curtain of reality.

Sacks documented his experiences with altered states in “Hallucinations,” including his famous weekend with morning glory seeds. He described how certain drugs could break the bonds of category and boundary in perception and also treated patients who reported mystical or revelatory experiences under the influence of various substances.

What could be “unlocked” when perceptual filters are temporarily disabled? Sacks approaches this question with scientific curiosity: could these experiences reveal aspects of brain function normally hidden? Lovecraft tells us: if our perception doesn’t allow us to see beyond, thank heaven, the door is to be left closed.

Sacks notes how even temporary experiences with drugs can leave “doors of perception” permanently altered. Lovecraft’s characters can never fully return to normality after their glimpses beyond the veil, they remain haunted by what they’ve seen.

The double-edged nature of this deliberate dissolution mirrors the neurological cases: gaining access to different realities means risking the stability of the one you’ve always known.

People who try mushrooms for example might have big problems or, during the trip, be able to unlock new bodily sensations and new abilities accessible even years later.

Neurophilosophy of Horror

Evolutionary psychology suggests that human perception evolved not for complete accuracy but for survival utility. We perceive what we need to navigate our environment, not necessarily what is really present. We are designed NOT to see certain aspects of reality, that our perceptual limits are a feature, not defects. If we reduce experience to mere biology, when we learn that our experience of a unified self is an illusion created by specialized brain modules, or that our decisions are made before we’re aware of them, we experience a milder version of the horror that Lovecraft’s characters feel when facing cosmic entities. What happens when the perception machine encounters something it cannot process? What are the limits of human understanding? And what lies beyond these limits?

In Strange Aeons even death may die

The boundary between normal and pathological perception is thinner than we’d like to admit. Our grasp on reality is tenuous. Sacks and Lovecraft ask us: if our reality can be so easily crumbled, by a stroke, a tumor, or an encounter with something genuinely alien to human experience, what is the nature of perception?

Perhaps the most unsettling parallel is this: Sacks’ case studies are based on real cases. The horror that Lovecraft imagined metaphorically, Sacks documented clinically.

These cases bring us, according to Sacks, “beyond the imaginary, into the mythical”. Or for Lovecraft, they bring us beyond the threshold of comfortable human knowledge, into realms where the mind itself begins to crumble, not in fiction, but in hospital rooms and neurological wards where reality itself becomes the ultimate cosmic horror. A cosmic horror that doesn’t lie in the vast immensities of the universe and its folds, but in the infinitesimal space between our neurons, maps of distant stars and a colder sky.

Post correlati

Short conversation with Margherita - flow state

Yesterday I had a conversation with Margherita, a person I know little and meet rarely.

Divinity is in the remix

The sacred doesn't live in perfection. It lives in the spaces between.

About grief

Grief is something you experience only once. It clings to you and gets woken up at random times. Maybe somebody else dies and it flares up, it's not new. Grief changes you in ways you cannot anticipate. I became a ticking time bomb.